Hip Dysplasia in Dogs

Hip dysplasia is abnormal development of the dog hip joint(s) as a puppy is growing. Importantly, the first, and hallmark characteristic of canine hip dysplasia is looseness (laxity) of the hips, not deformity of the bones of the joint. With loose hips, the ball part of the ball-and-socket joint slips and slides inside, and partially out of, the socket. This motion wears the dog’s cartilage, causes both the ball and the socket to become deformed, leads to osteoarthritis, and causes pain and impaired mobility. Some dogs show clinical signs of hip dysplasia with pain and lameness at that time, when they are puppies. Other dogs don’t show clinical symptoms of hip dysplasia until later in life when the cartilage loss and arthritic change becomes more severe. But, in all dogs with hip dysplasia, they have had hip dysplasia since they were a puppy. As a result, this presents an opportunity to diagnose and treat canine patients for hip dysplasia, either non- surgically or surgically, early in life.

How and when is hip dysplasia in dogs diagnosed?

Canine hip dysplasia can be diagnosed by physical exam in some patients, but is often confirmed by radiographs (X-rays). If a dog has palpable looseness (laxity) of the hip wherein the femoral head (ball part of the ball and socket joint) can half slide out of the joint (which it should not do), and this is felt on physical exam, then one can conclude the patient has hip dysplasia. This maneuver of testing laxity in dogs is called the Ortolani test and is generally performed under sedation. Most commonly, however, pain or discomfort with hip manipulation is all that is identified on initial physical exam. This is followed by radiographs (X-rays) of the dog’s hips. Importantly, there are different types of X-rays that can be made to diagnose hip dysplasia in dogs.

Hip radiographs (X-rays) to diagnose hip dysplasia in dogs

The most common radiographs made to evaluate dog hips are the traditional, “legs extended” view. These are also the type of radiographs that are reviewed by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) for grading. These radiographs are good, but imperfect. If these pelvic radiographs show a deformed hip, very loose hip, or an arthritic hip, one can confidently conclude that the dog hip is dysplastic. However, if the canine’s hips look good on these OFA radiographs, particularly in a puppy, there may still be laxity that just cannot be seen with these radiographs. That explains why OFA will not provide a grade on a dog’s hips prior to 2 years of age (unless the hips are obviously abnormal). This is due to the fact that these Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) style radiographs do not show hip looseness (laxity). As mentioned above, hip laxity is the first characteristic of hip dysplasia. Therefore, if the legs extended radiographs look very good, veterinary surgeons really want to know how lax (loose) the hips are. To know how loose the dog hips are, a veterinarian needs to take distraction radiographs.

Distraction radiographs, of which PennHIP radiographs are the most extensively studied and used, involve the physical distraction of the hips at the time of taking the X-ray to see how loose the dog hips are. From these PennHIP radiographs, the looseness is actually measured (called the distraction index; DI), not just subjectively estimated, and compared to the DI of many other dogs of only the same breed. With this information, a prediction is made as to the risk (ie probability) that your dog will develop hip osteoarthritis. These PennHIP distraction radiographs are most pertinent in assessing hips in young dogs that look good on the legs extended views. Knowing how loose those canine hips are, and the associated risk of developing osteoarthritis, can inform decisions on breeding that dog or on doing prophylactic surgeries to try and prevent the development of OA (see next).

Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) in Dogs

Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) is an extremely well-studied and substantiated surgery in dogs. It involves arresting the growth of the pubic growth plate when the puppy is young. As the rest of the dog’s pelvis continues to grow over the coming months, the sockets (of the ball and socket joint) grow to provide more coverage to the ball portion of the ball- and-socket joint. As a result, the ball cannot slip and slide out of the socket as easily. There is a lot known about this Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) surgery for dogs:

1. JPS is highly effective in puppies that have moderate or mild looseness of their hips. If their distraction index (DI) is greater than 0.7, JPS is less likely to be successful.

2. There is a very low complication rate of juvenile pubic symphysiodesis (JPS) in dogs and post-op recovery is short and relatively easy.

3. JPS really should be done by 15 weeks of age, maybe up to 18 weeks in giant dogs like Great Danes, in order to be effective.

The biggest “problem” with Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) is that few puppies and owners are aware of JPS or that it needs to be done by 15 weeks of age and as a result, many dogs are too old for JPS surgery by the time it is considered.

Double Pelvic Osteotomy and Triple Pelvic Osteotomy in Dogs

Double pelvic osteotomy (DPO) and triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) are very similar in concept to Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS). With DPO/TPO the pelvis is cut (with a saw) so that the socket can be rotated over top of the ball portion of the joint to provide more coverage to the ball. Hence, the ball is prevented from sliding (partially) out of the joint. The difference between DPO/TPO and JPS is that with JPS this coverage of the ball is increased gradually over time, and with double pelvic osteotomy (DPO) and triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) this is achieved immediately.

Dogs that are candidates for double pelvic osteotomy (DPO) and triple pelvic osteotomy (TPO) are typically young, about 5-11 months of age (approximately). Really, a dog is a candidate if the hips are well formed, and there is no osteoarthritic change yet, but the hips are loose (lax) and we know those dogs are at risk of developing osteoarthritis later in life.

Double and triple pelvic osteotomy are named as such because the pelvis is cut (osteotomized) either in 3 places (triple) or two places (double) in order to rotate that socket (one socket) over the ball. Triple pelvic osteotomy is the older way of doing it, double pelvic osteotomy has been used since 2006. In Dr. Franklin’s opinion, the evidence and experience show this is a really good hip dysplasia surgery for dogs that are good candidates, but the challenge is appropriately identifying patients that are good candidates. Many dogs already have osteoarthritic change and cartilage wear of the hips by the time they are diagnosed and hence are not candidates.

Dog with bilateral, staged double pelvic osteotomy (pre-operative and 8 weeks post)

Non-surgical management of Hip Dysplasia in Dogs

Non-surgical management of canine hip dysplasia can consist of many different things, but some are better supported by evidence. Those things are:

1. Restricting caloric intake and remaining thin. We know that both for puppies and adult dogs, limiting calories and staying light can minimize clinical symptoms associated with dog hip osteoarthritis.

2. Perform moderate, daily exercise to help the dog stay lean and fit.

3. Use oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if tolerated and as needed

4. Intra-articular joint injections, such as autologous protein solution

5. Use of anti-nerve growth factor (if they already have osteoarthritic hip joints, but not to be used in puppies with hip laxity). However, it should be noted that this is increasingly controversial with some catastrophic complications reported. We do not prescribe or use this at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics.

The area of non-surgical management that KC Canine Orthopedics has done the most research on and often helps primary veterinarians expand non-surgical management of canine hip dysplasia with are intra-articular injections. Please see our webpage here on sports medicine.

Femoral head ostectomy (FHO), Femoral head osteotomy (FHO), Femoral head and neck excision (FHNE) in Dogs

FHO and FHNE are just two different names (and abbreviations) for the same hip surgery in dogs. In this hip dysplasia surgery option, the femoral head and neck (ie the ball part of the ball-and-socket joint) are removed in order to eliminate any bone-on-bone, painful contact that can occur when the cartilage is worn. The canine patient is left without a true hip joint, but the limb is still attached to the body by numerous muscles and tendons that span the hip and attach to the pelvis. This is very similar to a dog’s front leg, which isn’t attached to the body by a boney joint but slides adjacent to the chest with numerous muscular attachments.

There are several attributes of Femoral head ostectomy (FHO), Femoral head osteotomy (FHO), Femoral head and neck excision (FHNE) that can summarize it and the post-op care succinctly.

- FHO or FHNE returns dogs, when done well, to about 80% of normal. This means that dogs do have some persistent pain or decreased mobility, but are often much improved if they had substantial pain and immobility prior to surgery.

- FHO or FHNE can be done at any age once the dog is an adult and so there is not a window of opportunity for performing an FHO or FHNE hip dysplasia surgery in dogs or cats.

- The complication rate with Femoral head ostectomy (FHO), Femoral head osteotomy (FHO), Femoral head and neck excision (FHNE) surgery is very low.

- Physical rehabilitation is very important following this FHO and FHNE surgery to help encourage dogs to use the limb, build strength and muscle mass, and maintain as much flexibility as possible.

Total hip replacement in Dogs

The other type of hip dysplasia surgery is Total hip replacement (THR). Total hip replacement in dogs involves the removal of the ball and the socket portion of the joint and replacement with a new ball-and-socket, hence “total” hip replacement. Total hip replacement (THR) in dogs is somewhat the opposite of FHO:

- Total hip replacement (THR) in dogs can provide near-normal or normal function. In other words, function and pain relief is superior to what can be achieved with FHO or FHNE

- Canine Total hip replacement (THR) is more expensive than FHO or FHNE.

- Total hip replacement (THR) in dogs has a low complication rate, but some complications can be very problematic and require removal of the implants. Complications of dog total hip replacement can include infection, dislocation, and fracture for example.

- Post-op care for canine Total hip replacement (THR) surgery in dogs requires restriction (ie rest and leashed walking) to try and avoid any of the aforementioned complications

Which is the Better Dysplasia Treatment: Femoral head ostectomy (FHO) or Total hip replacement (THR)?

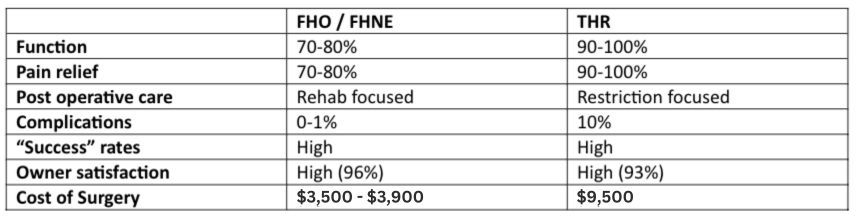

Most dogs are diagnosed with hip dysplasia after they are already mature, meaning that JPS and DPO are no longer options for them. In these cases, the two surgical options to treat hip dysplasia are FHO and THR. Often the question asked is: “What is best? The answer to this depends upon which criteria, for example, best pain relief and function, post-operative limitations, or cost, is most important. The following chart compares these two types of hip dysplasia surgery:

Hip Fracture in Dogs and Cats

Note that this discussion has been focused largely on canine hip dysplasia and associated osteoarthritis. However, some dogs and cats also suffer from hip fractures or hip dislocation (luxation). For fractures of the feline or canine femoral head or neck, the options can include:

- FHO or FHNE (see discussion above)

- THR (see discussion above)

- Fracture repair in select cases. Fracture of the femoral head and neck most commonly occurs in young dogs (and cats!) with fracture through the growth plate of the femoral neck. In these patients, fixing the fracture can be done, but usually has to be done within about 48 hours of the time fracture occurred. If a week has passed since the time of fracture, usually the options left include FHO or THR.

Hip Luxation/Dislocation in Dogs or Cats

Hip dislocation is a common hip injury in dogs. Importantly, the treatment options for canine hip dislocation vary depending upon the type of dislocation (craniodorsal vs. ventral). Over 90% of dislocated hips in dogs are craniodorsal luxations, so this discussion is focused on this type of luxation. The treatment options for craniodorsal hip luxation of the dog or cat include the following:

Closed reduction

Closed reduction is a non-surgical treatment for hip dislocations in dogs and cats that involves popping the dog or cat’s hip back into place and then slinging the hind leg. This is only an option if the canine or feline has a normal hip with no dysplasia. Even then, closed reduction has a low chance of success (less than 50%) and there are risk of complications.

FHO and THR Surgery

FHO and THR are common surgical treatment options for dogs or cats with hip luxation. See discussions above on Femoral head ostectomy (FHO), Femoral head osteotomy (FHO), Femoral head and neck excision (FHNE), and Total hip replacement

Hip Toggle

Hip toggle stabilization is an option for reducing a dog or cat dislocated hip and keeping it in place. It is only an option for a hip that does not have any dysplastic changes and no fractures. Hip toggles have a very high success rate, >90%. However, there is a chance (<10%) of re-luxation and the need for subsequent FHO or THR. Hip toggle is often Dr. Franklin’s preferred recommendation if the hip has no dysplastic changes.

Canine patient with a traumatic hip luxation treated with a TightRope Hip Toggle

Veterinary Services

Below are all of the veterinary services we offer at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics. If you have any questions regarding our services, please feel free to call us.