CRANIAL CRUCIATE LIGAMENT DISEASE

Important Points

The appropriate terminology for this ligament in veterinary medicine is cranial cruciate ligament (or CCL). However, both veterinarians and the public often refer to this as the anterior cruciate ligament (or ACL). Technically, the term ACL is appropriate for people but not dogs. However, the terms CCL, ACL, and “cruciate” are often used interchangeably in veterinary medicine.

Degeneration versus Traumatic Injury

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is the most common orthopedic abnormality in dogs. The term “disease” is used because in most dogs the ligament deteriorates over time, rather than tearing abruptly. In many dogs this process culminates with complete rupture of the ligament that appears to be a sudden injury, but it really is a culmination of the degenerative process. In a very small percentage of dogs (<1%) the ligament does ultimately rupture (tear) abruptly with trauma. What this means is that there are many different scenarios or histories for dogs with CCL disease or injury that include:

-

Sporadic lameness/limping that improves and gets worse in cycles. This process corresponds with the degeneration of the ligament, the associated inflammation in the knee that coincides with this degeneration, and the soreness that results from the inflammation and degeneration. At this stage the dog is often referred to as having a “partial tear”.

-

In many patients the aforementioned history then culminates with some dogs becoming lame abruptly and remaining lame. The sudden onset of abrupt and severe lameness often corresponds with complete CCL rupture.

-

Acute onset of lameness that is truly the result of trauma and that corresponds with rupture of the ligament without any preceding deterioration. This scenario is rare.

Diagnosis

When the ligament is completely ruptured it is easy to make a diagnosis of complete rupture based on physical examination because the knee is palpably unstable. However, when there is only a “partial” tear, the degree of instability can be subtle and subjective and it is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis based on the physical exam alone.

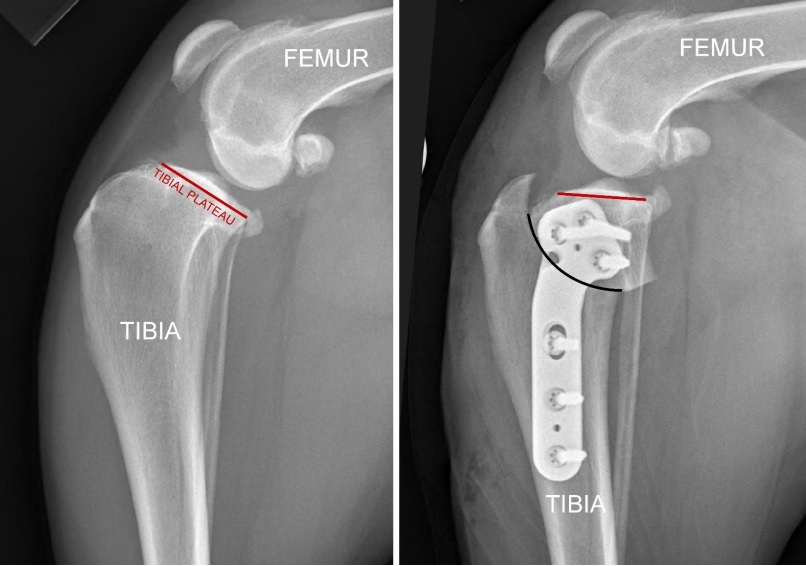

Radiographs (X-rays) provide additional information that can be helpful. It allows the veterinarian to see effusion (fluid) in the knee and bone spurs (osteophytes) around the knee, both of which indicate there is a problem in the knee. In some cases, one can also see that the femur (thigh bone) has slid backward on top of the tibia (shin bone), which does indicate CCL rupture. However, in cases of “partial rupture” there are times when both the physical exam and the radiographs are subtly abnormal. Since the CCL cannot be seen on an X-ray, the diagnosis is considered presumptive, or tentative, at this point.

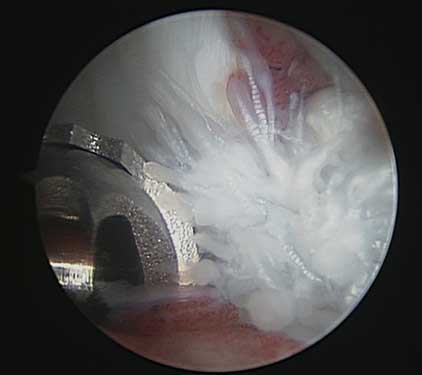

To confirm a diagnosis an MRI can be performed, and is frequently performed in people. However, in dogs MRI is rarely performed to assess the CCL. Rather, in most cases the diagnosis of CCL disease or rupture is made at the time of surgery as this is when the surgeon can see the CCL and confirm the diagnosis. There are two ways to do this. One way is to do an arthrotomy. This is where the surgeon incises and “opens” the knee to look inside with his/her naked eye. Conversely, the more advanced way to do this is to make a small incision and insert a camera (and arthroscope) and evaluate the interior of the knee, including the CCL, on a video screen. Arthroscopy provides a more thorough and less invasive way of evaluating the interior of the knee than does cutting the knee open to inspect it. One of the important points to take away is that the diagnosis of CCL disease or rupture is not confirmed until visualization of the CCL is performed. In rare cases of suspect “partial tear”, the CCL is found to be normal on inspection and some other problem is identified, such as an isolated meniscal tear, posterior cruciate ligament rupture, or cartilage injury. These other causes of lameness are far less common than CCL disease, but they can occur.

Treatment

There are numerous treatment options available for dogs with CCL disease. However, the preponderance of published research and evidence supports the following conclusions:

-

Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) is superior to non-surgical management and other surgical management techniques for treatment of partial or complete CCL rupture.

-

TPLO with partial tears can, but does not always, halt the degenerative process and preserve the intact portion of the CCL.

-

Meniscal tearing is consistently 10X more likely in dogs with complete CCL rupture than in dogs with partial CCL rupture. Further, cartilage damage is more severe in dogs with complete CCL rupture than in dogs with partial CCL rupture, likely because the meniscus is damaged. Progression of osteoarthritis is more rapid in dogs with complete CCL rupture. Therefore, it is preferrable to perform TPLO before the ligament completely ruptures in an effort to try and preserve the intact portion of the ligament, preserve the meniscus, and protect the cartilage.

-

Just because TPLO is medically superior, doesn’t mean other options are non-viable. Our surgeons, are willing to discuss other options, but are likely to specify the data supporting performing TPLO in dogs with partial or complete CCL rupture.

WHAT IS TIBIAL PLATEAU LEVELING OSTEOTOMY

The TPLO is a procedure in which the tibia (shin bone) is cut, re-oriented, and stabilized to provide improved stability to the knee. Basic information can be found on this procedure here: https://kck9ortho.com/acl-tplo-shawnee-ks/

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis with TPLO is excellent. Approximately 94% of owners of dogs treated with TPLO ultimately report a good or excellent outcome.

POTENTIAL COMPLICATIONS

Major complications with TPLO are infrequent. Our surgeons have performed thousands of TPLOs dating back to 2009 and the re-operation rate is less than 1%. However, numerous complications are possible and include infection (most common), tearing of the meniscus weeks or months following TPLO, incisional complications like bruising or fluid accumulation, fracture of the tibia, inflammation of the patella tendon, anesthesia-related complications including death, and others.

Recovery

Since the tibia (shin bone) has been cut and stabilized, the first major objective following surgery is to have the tibia (shin bone) heal without complication. It usually takes bone 8-12 weeks to heal with most dogs having substantial healing by 8 weeks post-operatively. Additional time is needed for the dog to reach their full potential. A brief review of post-op timelines includes:

-

2 weeks post-op: The incision is healed. The dog should be “toe-touching” on the limb at this point most of the time when walking.

-

During month 1: The patient is allowed to walk about 15-30 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb >90% of the time when doing so by the end of the first month.

-

During month 2: The patient is allowed to walk 30-45 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb the vast majority of the time, although not entirely normally.

-

8 weeks: Radiographs (X-rays) are usually checked at about this time to make sure that the bone is healing appropriately and most dogs have about 85% healing of their bone at this point in time.

-

During month 3: Most dogs need to get “back in shape”. They can have extensive leashed walking, jogging, and hiking during this month. Moderated and supervised periods of off leash running and play can be performed during this month.

-

End of month 3: Dogs are usually released to unlimited activity at the end of month 3.

SUMMARY POINTS

-

CCL disease is the most common orthopedic abnormality in dogs

- Physical exam, radiographs (X-rays), and visualization of the CCL , preferably with arthroscopy, are all important in confirming a diagnosis of CCL disease.

- TPLO is the most thoroughly researched and supported treatment of CCL disease in dogs.

- Prognosis with TPLO is excellent and major complications are infrequent but all owners should be aware of the possibility of complications.

- Recovery period is 3 months with the dog having minimal, moderate, and substantial activity in months 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

- A reasonable resource on CCL disease can be found on the website of the American College of Veterinary Surgeons: https://www.acvs.org/small-animal/cranial-cruciate-ligament-disease. Note that while Kansas City Canine Orthopedics does not agree with all statements or recommendations on that website, KCCO refers you to that website to provide additional information as a resource for pet owners.

Featured Video

Veterinary Services

Below are all of the veterinary services we offer at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics. If you have any questions regarding our services, please feel free to call us.