Canine Shoulder Disorders

Injuries to the canine shoulder can cause significant pain and lameness in dogs, impacting their quality of life. Various structures within and around the dog shoulder are susceptible to injury, and the conditions affecting them can differ in terms of treatment. This guide provides an overview of the most common shoulder injuries in dogs and the treatment options available.

Osteochondrosis and Osteochondritis Dissecans in Dogs

Osteochondrosis (OC) and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) are conditions that affect the shoulder joints of any growing animal including humans, horses, and dogs. Osteochondrosis is a developmental disorder in which the cartilage of the immature skeleton does not properly mature or develop into bone. As a result, there is a thickened area of cartilage.

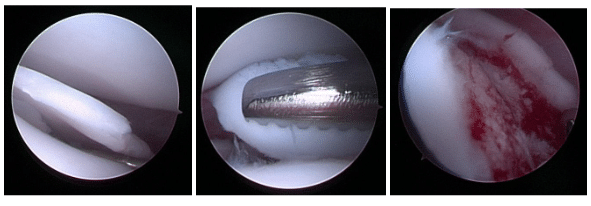

This thickened cartilage begins to detach from the underlying bone, just as can be seen in the picture, and this is painful. The only difference between osteochondrosis and osteochonditis dissecans (OCD), is that OCD is when that flap of cartilage actually becomes or starts lifting up away from the underlying bone, but the underlying process is the same.

In dogs, numerous joints can be affected including the shoulder, elbow, stifle (knee), or ankle (tarsus). The shoulder is the most commonly affected, and fortunately, dogs with shoulder OCD can be treated with a very good prognosis. Those different treatments include non-surgical management, open debridement, arthroscopic debridement, synthetic resurfacing, or osteochondral allograft transplantation. We will discuss each briefly below:

Non-Surgical Management of Osteochondrosis and Osteochondritis Dissecans

In general, non-surgical management is not recommended and is not the standard of care for patients with pain and lameness attributable to shoulder OC/OCD. However, it is interesting that in a textbook from the 1980s, it was recommended to exercise such dogs very vigorously to try and break that cartilage flap off and have it float somewhere else in the joint.

Part of the reason this is not recommended today is because we do occasionally see dogs where this has happened and where the flap has floated somewhere that is causing pain and lameness, but which is not readily accessible in veterinary surgery, making finding the flap and removing it exceedingly difficult. Today, most canine shoulder injuries are managed surgically if symptoms of dog shoulder pain and lameness persist, to avoid complications.

Open debridement

In this surgical method, the dog shoulder joint is opened to remove damaged cartilage. While effective, it’s fallen out of practice in favor of arthroscopic debridement, which is minimally invasive. (We encourage all owners to look at our webpage discussing the differences between arthrotomy and arthroscopy. In brief, arthrotomy is where the joint, in this case the shoulder, would have a large incision made with a scalpel blade so the veterinary surgeon can look inside the shoulder with his/her naked eye.)

In open debridement, the cartilage flap is removed (debrided) and the remaining bone bed is scraped and cleaned to leave a fresh bed in which new fibrocartilage can grow. The cartilage that fills in the defect is neither complete, nor perfect, but the prognosis for resolution of lameness is very high in dogs with shoulder OC/OCD.

On the right is an image of an open arthrotomy for a dog shoulder OC/OCD, with the right image showing the defect after debridement. The image is grainy and pixelated because open arthrotomy is rarely done these days, with modern orthopedic veterinary surgeons preferring minimally invasive arthroscopy.

Arthroscopic Debridement

Arthroscopic debridement is the same in principle as open debridement. The flap of cartilage is removed, the remaining bone bed is scraped to clean it and facilitate bleeding, and the defect fills in (to some degree) with healing fibrocartilage. The difference between this and open debridement is that arthroscopic treatment means this is performed entirely with an arthroscope through two or three small incisions (each about 5-8 millimeters long).

At Kansas City Canine Orthopedics, minimally invasive arthroscopy is preferred for treating OCD-related dog shoulder injuries, reducing recovery time and pain. This method allows for the surgical removal of the OCD flap and debridement to be done with two small incisions, which causes less pain and disruption to the underlying muscles. A very high percentage of dogs undergoing arthroscopic removal of their OCD flaps do very well afterward.

Synthetic resurfacing

Synthetic resurfacing in dogs involves an open approach, removing the cartilage flap, then drilling out the defect to create a uniform, cylindrical socket. Then, a synthetic “plug” or cylinder with a metal base and rubber cap (SynACART) is placed into the socket to fill the defect.

Osteochondral allograft transplantation (OCAT)

Osteochondral allograft transplantation is the exact same in concept and execution as the synthetic resurfacing described immediately above. However, instead of using a metal and rubber implant, one uses a cylinder of bone and cartilage provided by a donor dog that is deceased. This process is performed uncommonly in the canine shoulder. Below are images of performing an OCAT to treat an OCD in a canine knee; the process is the same for the shoulder:

In summary, canine shoulder OC/OCD is a common cause of front leg lameness in young dogs. Fortunately, most dogs do very well with arthroscopic debridement alone. Following such surgery the biggest challenge is keeping the puppies rested as most feel much better within just 2 weeks following veterinary surgery.

Biceps Tendon Issues in Dogs

The biceps brachii tendon, which connects the biceps muscle to the bones of the shoulder, can often become injured and be a source of pain, lameness and reduced range of motion, particular in German Shorthaired Pointers. Disorders of the dog bicep tendon can range from tendinitis (inflammation of the tendon), bicipital tenosynovitis (inflammation of the sheath) to tendon rupture. If orthopedic examination isolates pain to the dog shoulder, additional diagnostics may include minimally invasive arthroscopy, musculoskeletal ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Tendons are not visualized on radiographs (X-rays) however radiographs may be used to evaluate the shoulder for other differentials of shoulder pain.

Treatment options for biceps tendon injury in dogs depend on the underlying disorder. Medical management often includes physical rehabilitation and the use of oral medications such as non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or intra-articular injections such as hyaluronic acid, steroids or platelet rich plasma (please see our associated pages on sports medicine, joint injections, and orthobiologics). Surgical treatments for canine biceps tendon disorders may include arthroscopic biceps release, or relocation of the biceps with re-attachment just slightly below the shoulder joint (also known as tenodesis). Of these, the most common treatment(s) in dogs are either non-surgical management with injections.

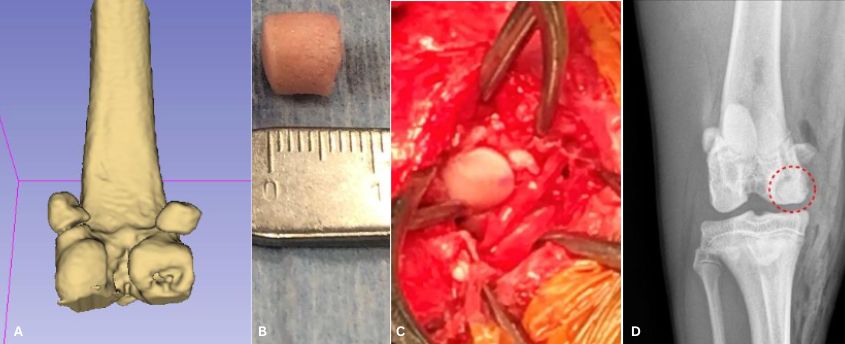

Image of a healthy dog biceps tendon.

Visual assessment identifies an injured canine biceps tendon, consistent with a partial avulsion. Concomitant synovitis is noted, indicative of significant joint inflammation.

Canine Supraspinatus Tendon Issues

The canine supraspinatus is one of the rotator cuff muscles and plays a crucial role in shoulder stability and movement. In dogs with shoulder pain, the supraspinatus is commonly suspected as being the causenor culprit. Confirming this diagnosis is difficult but the diagnostic process can be aided with X-rays, CT scans, ultrasound, MRI, and minimally invasive arthroscopy.

The X-ray (radiograph) below (to the left) shows a dog supraspinatus with mineralization within it and the post-operative image (to the right).

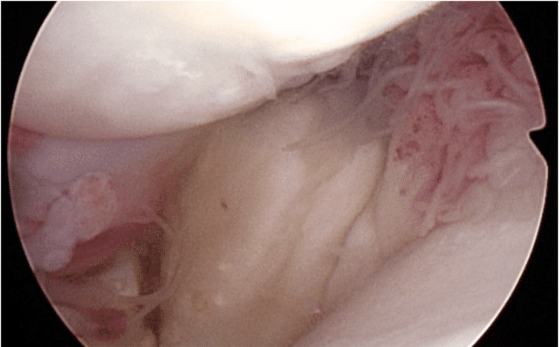

Most cases of supraspinatus tendinopathy do not have mineralization like the case above, and hence are not diagnosed with X-rays (radiographs). Most cases require use of ultrasound, MRI, or diagnostic arthroscopy for diagnostic confirmation. The arthroscopy images below show an enlarged supraspinatus tendon in a canine impinging upon the biceps tendon. The canine supraspinatus is pushing the biceps from right to left.

Most dogs with supraspinatus tendonopathy do not need surgical

treatment, but rather are medically managed with physical rehabilitation, the use of oral medications such as non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or intra-articular injections such platelet rich plasma (please see our associated page on PRP and stem cells injections).

Medial Shoulder Instability (MSI) in the Dog

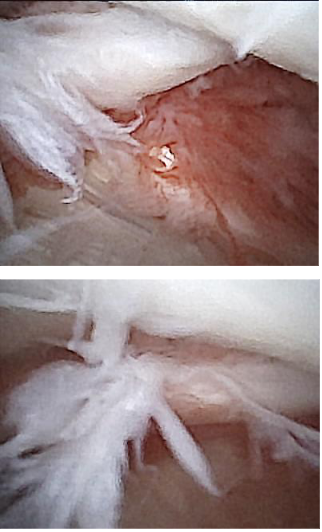

Some dogs, particularly active competitors or working dogs, strain the inside of their shoulder (the medial glenohumeral ligament, subscapularis tendon). The best way to make a diagnosis of medial shoulder instability is to perform minimally invasive arthroscopy and look inside the shoulder at the medial structures. Fortunately, Kansas City Canine Orthopedics can do this with a very small arthroscope (nanoscope) that provides excellent visualization and diagnosis. The images to the right show mild fraying and tearing of a medial glenohumeral ligament.

Subsequently, some dogs may need specialty surgery to stabilize their shoulder. Dr. Sam Franklin has performed and published on surgical treatments of Medial Shoulder Instability. Fortunately, many dogs don’t need surgical stabilization. Rather, once the diagnosis is confirmed with arthroscopy, many dogs are treated with non-surgical management with physical rehabilitation, the use of oral medications such as non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or intra-articular injections such as hyaluronic acid, steroids or platelet rich plasma. Please see our page on injections and orthobiologics.

Veterinary Services

Below are all of the veterinary services we offer at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics. If you have any questions regarding our services, please feel free to call us.