Overview of Patella Luxation in Dogs

The patella is the medical term for the kneecap. The canine patella is located inside the quadriceps, which is the large muscle mass on the front of the thigh that enables dogs to stand up, jump, and run. The dog patella helps the quadriceps perform these functions by acting as a fulcrum that slides back and forth in a groove (the trochlea) on the front of the knee, enabling the quadriceps to make a sharp bend when the knee is bent.

Unfortunately, some dogs develop an alignment problem and the patella starts popping in and out of that groove. When that happens, the quadriceps of the dog knee cap cannot function normally, cartilage on both the patella and the trochlear groove becomes damaged, and the luxation hurts. Consequently, the misalignment should be addressed to get the dog patella to move smoothly back and forth in the groove without popping out of the groove.

There are several different ways luxating patella surgery in dogs can correct this condition, such as:

- Deepening the trochlear groove so that the dog patella sits more deeply and is less likely to pop out

- Shifting the alignment of the quadriceps mechanism, by adjusting its attachment site (the tibial tuberosity), so that it keeps the dog patella in place

- Adjusting the ligaments that hold the dog patella in place

- Straightening a curvy, bow-legged femur (thigh bone)

If you want to dig deeper into the details of dog patellar luxation please keep reading below.

What is Medial Patellar Luxation (MPL) in Dogs?

Medial patellar luxation (MPL) is the medical term for patella luxation (or disclocation) in dogs. It’s a common orthopedic condition in dogs where, to put it simply, the patella (kneecap) slips out of its natural groove on the inner (medial) side of the knee, causing discomfort and restricted movement.

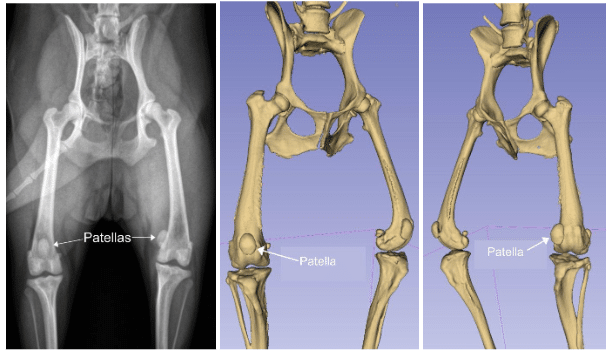

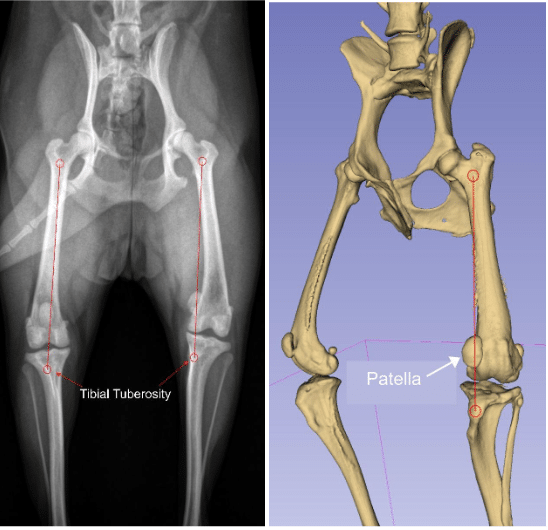

The radiograph (X-ray) above (to the left) shows one dog patella in its appropriate location over the front of the knee in the trochlear groove, while the other dog patella is luxated medially (to the inside of the knee) and out of the trochlear groove. The three-dimensional (3D) virtual models made from a computed tomography (CT) scan shows the right canine patella in place (middle image above) and the left canine patella luxated (image to the left).

What are the Clinical Signs or Symptoms of Patellar Luxation?

Dogs with MPL (luxating patella) can have varied clinical signs, but the most common is simply a decreased use of the affected leg(s) with occasional lameness. Some dogs will intermittently hop or skip when the patella is out of place, attempting to pop it back into position (due to it not tracking in the trochlear groove correctly). Sometimes the dogs will then kick their legs back behind them to try and pop the patella back into place.

Cause and Development of Patella Luxation

Luxating patella in dogs usually develops between 6–12 months of age (even though clinical symptoms of luxating patella are often unnoticed until later; see below). And, although there is a genetic contribution to the development of patella luxation—with some dog breeds having a higher disposition for patella luxation—dogs are very rarely born with patella luxation. Finally, it is uncommon to have a dog with an “injury” that causes patella luxation.

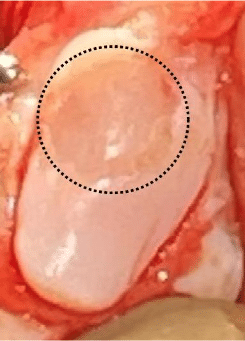

Despite the fact that the majority of dogs with patella luxation first have luxation when they are young, many owners will not notice clinical symptoms until later in life. This may be because the patella luxation starts out as being relatively infrequent. However, as the dog patella pops in and out of the groove it abrades the side of the groove (ie the ridge) and the cartilage on the patella. Over time, the cartilage gets worn down, both on the ridge and the patella. In fact, 66% of dogs who have patella luxation have full thickness cartilage wear lesions on their patella, ouch! As the ridge gets worn down, it becomes shorter and is less capable of preventing luxation of the patella and the patella luxation occurs more frequently.

Hence, many dogs may not have clearly recognizable symptoms of luxating patella at first, and the condition may go unrecognized until they are 3-5 years of age, even though the patella luxation first started happening when they were young.

The above photo shows a substantial loss of cartilage from the underside of the patella in a canine patient with patella luxation. Cartilage loss is common on both the dog’s patella and trochlear ridge.

Grading Patella Luxation and Treatment Options

Canine or feline patella luxations are graded 1 through 4:

Grade 1 Patella Luxation – The patella can be manually pushed out of the groove, but otherwise stays in the groove.

Grade 2 Patella Luxation – The patella is in the groove most of the time, but will luxate out of the groove on its own.

Grade 3 Patella Luxation – The patella is usually out of the groove, but will spend some time in the groove.

Grade 4 Patella Luxation – The patella is permanently out of the groove and cannot even be manually pushed back into the groove.

Although the grading system is not the be all and end all for decision making regarding patients, it does provide a framework for recommendations. In general, Dr. Sam Franklin believes that the vast majority of canine patients with grade 2 luxating patella or higher should have the patella stabilized. This is because, as discussed above, the luxation often causes progressive wear and degeneration of the joint over time, grinding down the trochlear ridge and the cartilage on the patella. Hence, it is preferrable to stabilize the pet’s patella before such cartilage and bone wear occurs. And, although muscle strengthening is sometimes combined with dynamic knee braces in people to help try and control low grade patella luxation, the cause and severity of the luxation in people is different.

This probably explains why there is no evidence that any luxating patella dog brace or rehab alone can successfully correct patella luxation in dogs with grade 2, 3, or 4 luxations. In turn, this is why veterinary surgeons tend to recommend MPL surgery for dogs with clinical symptoms that have grade 2, 3, or 4 luxations. Conversely, for grade 1 luxation, those patients should not have surgery, in our opinion. Continued exercise and muscle strengthening might not be needed for these dogs, but could be beneficial.

Surgical Treatment Options for Patellar Luxations:

MPL surgery is often recommended to correct patella luxation in dogs, especially in cases where dislocation is frequent or causes significant pain. Left untreated, MPL/luxating patella can lead to further joint damage, reduced mobility, and chronic pain. Medial patellar luxation (MPL) surgery in dogs is specifically designed to reposition the patella, allowing the joint to move properly and preventing recurring dislocations.

As discussed briefly above, there are different ways to surgically stabilize the cat or dog patella including, but not limited to:

- Deepening the trochlear groove so that the patella sits more deeply inside and is less likely to pop out, called a

trochleoplasty. - Shifting the alignment of the quadriceps mechanism so that it keeps the patella in place, termed a tibial tuberosity

transposition or TTT - Tightening and loosening the ligaments/soft tissue that hold the patella in place

- Straightening a malaligned (i.e. curved) femur

Of these options, the most common for dogs with patella luxation is to perform surgical options 1 through 3. Let’s look more closely at these surgical procedures.

Trochleoplasty for Patella Luxation:

There are numerous different ways to perform a trochleoplasty but the general idea is typically the same for all methods and involves making the groove deeper so the patella sites deeper into the groove. The below examples show how a block or wedge of bone and cartilage can be removed temporarily from the pet’s groove, extra bone below the block/wedge is removed, and then the wedge or block is placed back but it sits deeper.

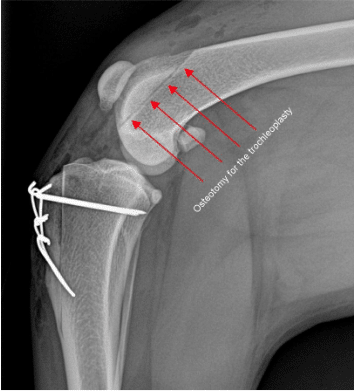

The figure above shows the osteotomy (cutting of the bone) where the trochleoplasty was made for a dog with medial patella luxation.

Tibial tuberosity transposition (TTT) for Patella Luxation

As stated above, the dog patella is located within the quadriceps muscle mass on the front of the thigh. The quadriceps wants to run a relatively straight line between its two attachment sites, at the top of the femur (thigh bone) down to the patella, and then via the patella tendon to the bump on the front of the shin bone (tibia) referred to as the tibial tuberosity. Often, the tibial tuberosity is not aligned with the trochlear groove. That means that the patella is not in line with the groove and is more likely to luxation.

Femoral Varus and Femoral Osteotomy

In some cases, luxating patella dog surgery includes a femoral osteotomy to correct bow-legged deformities in the femur. In a few dogs the patella is not aligned with the trochlear groove because the femur is curvy or bowlegged. In these cases, the quadriceps runs its straight line from the top of the femur to the tibial tuberosity but this does not align with the trochlear groove.

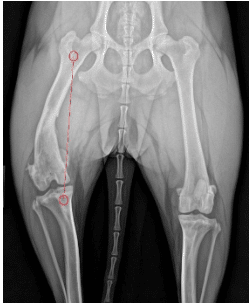

The radiograph (X-ray) to the left shows a dog with a severe bowlegged deformity and patella luxation.

In these dogs, the solution to the patella luxation involves straightening the thigh bone (femur) by cutting the femur, removing a wedge section, and then securing the femur back together with a bone plate and screws. The bone then heals over the next 10-12 weeks. The bone plate and screws could be removed, but are almost always left in place.

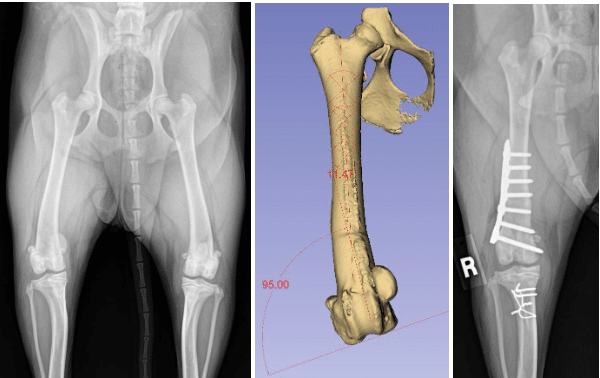

The radiograph (X-ray) image below left shows a dog with patella luxation affecting the right knee (stifle). This patient has about 11° of extra curvature to the femur. The center image below shows the three-dimensional (3D) model of that dog’s bowlegged right femur and measurements of the curvature. The radiograph (X-ray) below right shows the dog’s femur immediately following surgery in which the femur has been cute and bone plate and screws have been used to straighten the dog’s femur.

Assessing Bowlegged Conformation (Femoral Varus)

Very few dogs with medial patella luxation (fewer than 10%), have such bowlegged femurs that they need their femur straightened. But, accurately identifying dogs that need their femur straightened is important because if the dog has a bowlegged femur and this is not addressed, the patella may re-luxate within the first 12 weeks following surgery in which the femur is not straightened. Unfortunately, veterinary surgeons cannot accurately determine if the femur is bowlegged at the time of surgery (ie “once we get in there”) because we are not exposing the entire femur during surgery. We also cannot consistently and accurately assess whether the femur is bowlegged using radiographs (X-rays) because the femur needs to be perfectly positioned for such X-rays and dog anatomy makes this difficult. Consequently, many dogs appear to be bowlegged on X-ray, but really are not. The most accurate way to assess whether the femur is curvy is to do a computed tomography (CT) scan, create a 3D virtual model of the patient’s leg, and measure the curvature directly from this model.

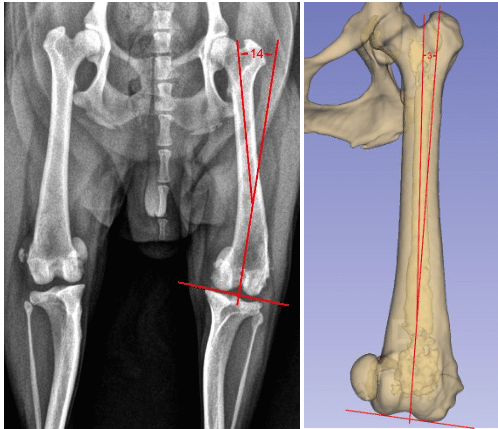

The images to the right are both from the same dog and both show the patella luxated. The radiograph (X-ray) above left, shows about 14 degrees of femoral varus (ie

bowlegged curvature to the femur), which is severe enough to warrant consideration of a femoral straightening. However, that measurement from the dog’s X-ray is inaccurate. The 3D reconstruction from the CT scan, which is a superior way for measuring femoral curvature, shows this patient really only has about 3 degrees of excess curvature and does not need the femur straightened.

- Any dog with a grade 4 medial patella luxation (MPL). Dogs with grade 4 luxation very frequently have notable deformity (e.g. femoral curvature) that requires straightening.

- Dogs with high grade 3 medial patella luxation, particularly if they appear bowlegged.

- Dogs that have an apparent fracture deformity of their femur (malunion) with associated bowlegged conformation

Dogs that could have a CT scan, but probably do not need a CT scan or femoral osteotomy are:

- Small breed dogs with grade 3 medial patella luxation (MPL) that the femur appears straight based on radiographs (X-rays)

Dogs that really do not need a CT scan:

- Any dog that has just a grade 2 medial patella luxation. These dogs rarely have such severe deformity as to warrant CT scan or femoral osteotomy

Following CT a 3D virtual model is made (see 3D virtual models above), measurements of the conformation or alignment are made, and decision regarding whether a femoral osteotomy are discussed and made with the owner. Surgery can then be performed with confidence that preparation is complete and all relevant steps have been taken to optimize the chance of a successful patellar luxation surgery.

Prognosis / Success Rate of Patellar Luxation Surgery

The prognosis with canine medial patella luxation surgery is excellent. Approximately 95% of dogs function very well, returning to their former level of activity and play without any patella luxation.

Potential Complications of Patellar Luxation Surgery

Major complications with MPL surgery are very infrequent. However, numerous complications are possible and include patella reluxation (which would occur within the first 12 weeks following surgery), failure of the pins and wires to hold a tibial tuberosity together, infection, incisional complications like bruising or fluid accumulation, or anesthesia-related complications including death, and others. Also, a very small percentage of patients find the pins and wire uncomfortable and we perform a minor procedure to remove them once the tibia tuberosity is healed.

Following Patella Luxation Surgery

Once MPL surgery is performed the bones that have been cut need to heal, as do any of the associated soft tissues. This takes time, typically about 10 weeks. Additional time is needed for the dog to reach their full potential. The following is a broad overview of the timeline of recovery and does not serve as a set of specific discharge instructions. Detailed discharge instructions are provided to pet owners separately.

A brief review of post-op timelines for dog patellar luxation surgery includes:

- 2 weeks post-op: The incision is healed. The dog should be at least toe-touching on the limb when walking, if not bearing more weight.

- During month 1: The dog is allowed to walk about 15-30 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb >90% of the time when doing so by the end of the first month.

- During month 2: The dog is allowed to walk 30-45 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb the vast majority of the time, although not entirely normally.

- 8 weeks: Radiographs (X-rays) are usually checked at about this time to make sure that all bones are healing appropriately and most dogs have about 85% healing of their bone at this point in time.

- During month 3: Most dogs can have extensive leashed walking, jogging, and hiking during this month. Brief, moderated, and supervised periods of off leash running can be started during this month.

- End of month 3: Dogs are usually released to unlimited activity at the end of month 3.

Summary Points for Patella Luxation in Dogs

- Medial patella luxation (MPL) is a very common orthopedic abnormality in dogs

- Physical exam, radiographs (X-rays), and possibly CT scan, are used to confirm a diagnosis and plan surgery for patellar luxation correction.

- Prognosis with dog MPL surgery is excellent and major complications are infrequent but all owners should be aware

of possible complications. - The recovery period is 3 months with the dog having minimal, moderate, and substantial activity in months 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

Veterinary Services

Below are all of the veterinary services we offer at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics. If you have any questions regarding our services, please feel free to call us.