TPLO Surgery in Dogs

Expert TPLO Surgery for Dogs in the Kansas City Area

At Kansas City Canine Orthopedics, we specialize in Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO) surgery, a leading treatment for dogs suffering from cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) injuries. If your dog is limping, struggling to stand, or unable to enjoy their favorite activities, TPLO surgery can provide lasting pain relief and restore mobility. Our Shawnee, KS veterinary team offers advanced orthopedic care, including minimally invasive surgery and diagnostics, ensuring the best possible outcome for your pet.

Cranial Cruciate Ligament Disease

Brief overview:

The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) in a dog’s knee (often called the “dog ACL”) plays a critical role in stabilizing the knee joint by preventing the femur (thigh bone) from sliding off the tibia (shin bone). This ligament deteriorates over time in dogs and often culminates with complete rupture (break/tear) of the ligament and an unstable knee. CCL deterioration or injury can lead to pain, instability, and difficulty walking. Unlike sudden ACL injuries in humans, CCL disease in dogs often progresses gradually, weakening the ligament before it fully ruptures.

How We Diagnose CCL Disease in Dogs

Early detection is key to preventing further joint damage. Our orthopedic specialists use a combination of:

- Physical exams to assess knee stability and range of motion

- X-rays to rule out fractures and evaluate joint health

- Arthroscopy (minimally invasive joint evaluation) for precise diagnosis

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, we address this problem by cutting the tibia (shin bone) and re-aligning it so that the knee is stable and the femur (thigh bone) does not slide off the back of the tibia (shin bone). Once the tibia is healed from this procedure, usually 10-12 weeks following surgery, most dogs (95%) can go back to running, jumping, playing and doing the things they love to do.

Signs of CCL Disease in Dogs

Dogs may show different signs of CCL disease. Here are some of the signs your dog may have a CCL injury:

- Limping or sudden lameness in one or both hind legs

- Stiffness after exercise or long rest periods

- Difficulty getting up after lying down,

- Difficulty jumping or climbing stairs

- Sitting with one leg stretched out to the side (positive sit test)

- Swelling or instability in the knee joint

How to Do The “Sit Test” for CCL Disease

One easy way that owners can assess if their dog might have CCL is by looking at how their dog sits. This is called the sit test. A normal dog should sit squarely on his/her rump with his or her knees directly under her body. Dogs with CCL disease have discomfort bending their knees fully so they roll over onto their rump and place their legs out to the side. If a dog sits like this they are said to “fail the sit test”. There are different explanations for failing a sit test, but the most common is CCL disease.

What Causes CCL Disease?

Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL) disease is a leading cause of knee pain and mobility issues in dogs. It can develop due to gradual degeneration over time or an acute injury, ultimately leading to joint instability. Understanding the key risk factors can help pet owners recognize early signs and seek timely veterinary care.

CCL disease can result from progressive ligament weakening or sudden trauma. Contributing factors include:

- Breed predisposition – Large and medium-breed dogs, such as Labradors, Rottweilers, and Boxers, are more susceptible.

- Excess weight – Additional strain on the knee joint accelerates ligament wear.

- High activity levels – Repetitive running, jumping, or abrupt movements can weaken the ligament.

- Age-related changes – Over time, the ligament naturally deteriorates, increasing the risk of injury.

Recognizing these risk factors can help with early diagnosis and intervention, improving long-term joint health and mobility.

Understanding CCL Disease and Injury

Terminology: Dog ACL vs. CCL

The appropriate terminology for this ligament in veterinary medicine is the cranial cruciate ligament (or CCL). However, both veterinarians and the public often refer to this as the anterior cruciate ligament (or ACL). Technically, the term ACL is appropriate for people but not dogs. However, the terms CCL, ACL, and “cruciate” are often used interchangeably in veterinary medicine so do not be confused when these different terms are used.

CCL Degeneration vs. CCL Injury

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is the most common orthopedic abnormality in dogs. The term “disease” is used because in most dogs the ligament deteriorates over time, rather than tearing abruptly. In many dogs this process culminates with complete rupture of the ligament that appears to be a sudden injury, but it really is a culmination of the degenerative process. In a very small percentage of dogs (<1%) the ligament does rupture (tear) abruptly with trauma when it was completely normal just moments before. What this means is that there are many different scenarios or histories for dogs with CCL disease or injury that include:

-

- Sporadic lameness/limping that improves and gets worse in cycles. This process corresponds with the degeneration of the ligament, the associated inflammation in the knee that coincides with this degeneration, and the soreness that results from the inflammation and degeneration. At this stage the dog is often referred to as having a “partial tear”.

- In many patients the aforementioned history then culminates with some dogs becoming abruptly lame and remaining lame. The sudden onset of abrupt and severe lameness often corresponds with complete CCL rupture.

- Acute onset of lameness that is truly the result of trauma and that corresponds with rupture of the ligament without any preceding deterioration. This scenario is rare.

CANINE KNEE ANATOMY

Basic Structure of the Canine Knee

Basic Structure of the Canine Knee

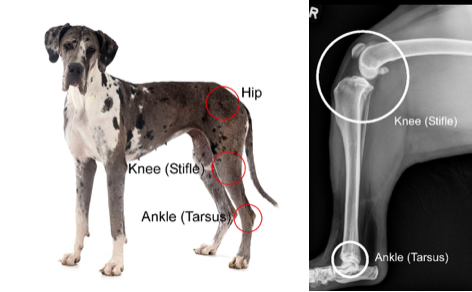

First, we need to understand some basic anatomy. The dog ACL or cranial cruciate ligament is in the knee (stifle) of dogs.

To the left, please see a Great Dane showing where the knee is located and an X-ray (radiograph) showing where the dog’s stifle (knee) is located.

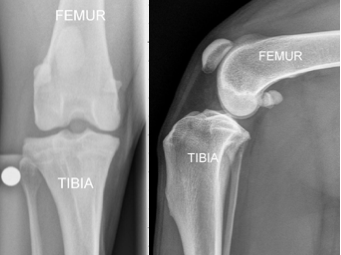

The knee in the dog basically comprises two bones with the femur resting on top of the shin bone (tibia). There is a smaller third bone (fibula), but the fibula is not relevant to this topic.

The radiographs to the right show the front view of a dog knee. The radigoraphs on the right, show a dog’s knee anatomy from the side view. The dog’s femur (thigh bone) is on top of the tibia (shin bone).

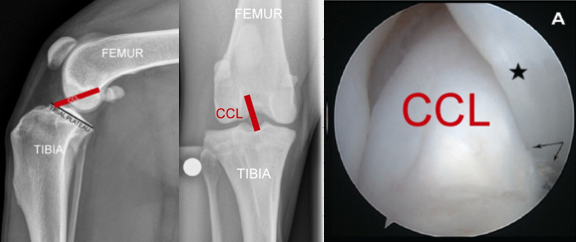

The Role of the Cranial Cruciate Ligament

The femur does not normally slide off the back of the tibia because the canine ACL (CCL) holds it in place. The CCL is inside the knee and is a stout ligament that is oriented specifically to prevent the dog’s femur from sliding off the back of the tibia (or from the tibia from sliding forward out from under the femur). See next.

What Happens When the CCL Ruptures?

When the dog’s CCL ruptures, the femur can then slide off the back of the femur.

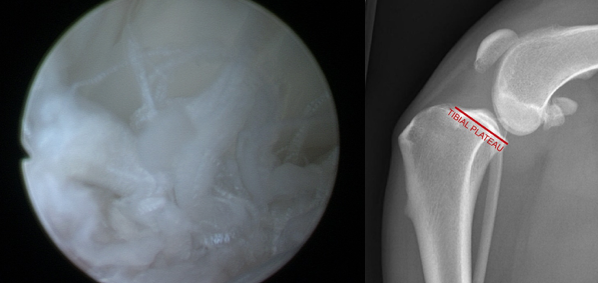

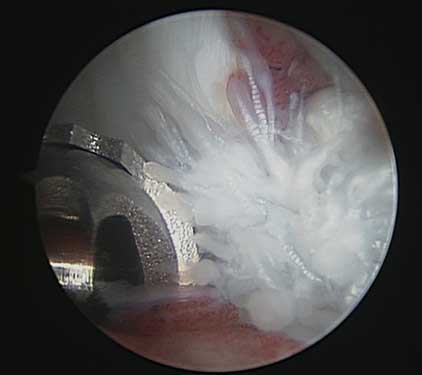

The image to the left is an arthroscopic image looking at a dog’s ruptured (torn) cranial cruciate ligament. It looks like the ends of a mop. On the right we can see that the femur is sliding off the back of the tibia, which is why procedures like TPLO surgery (aka “dog ACL surgery”) are necessary to stabilize the knee after a CCL rupture.

Diagnosis of Canine CCL Disease

When the cranial cruciate ligament is completely ruptured, it is easy to make a diagnosis of complete rupture based on a physical examination of the dog because the knee is palpably unstable. However, when there is only a “partial” tear, the degree of instability can be subtle and subjective and it is not possible to make a definitive diagnosis based on the physical exam alone.

Radiographs (X-rays) provide additional information that can be helpful. It allows the veterinarian to see effusion (fluid) in the dog’s knee and bone spurs (osteophytes) around the knee, both of which indicate there is a problem in the knee. In some cases, one can also see that the femur (thigh bone) has slid backward on top of the tibia (shin bone), which does indicate CCL rupture. However, in cases of “partial CCL rupture,” there are times when both the physical exam and the radiographs are subtly abnormal. Since the CCL cannot be seen on an X-ray, the diagnosis is considered presumptive, or tentative, at this point.

To confirm a diagnosis an MRI can be performed, and is frequently performed in people. However, in dogs, MRI is rarely performed to assess the CCL. Rather, in most cases, the diagnosis of CCL disease or rupture is made at the time of surgery as this is when the surgeon can see the CCL and confirm the diagnosis.

There are two ways to do this. One way is to do an arthrotomy. This is where the surgeon incises and “opens” the knee to look inside with his/her naked eye. Conversely, the more advanced way to do this is to make a small incision, insert a camera (and arthroscope), and evaluate the interior of the knee, including the CCL, on a video screen.

Arthroscopy provides a more thorough and less invasive way of evaluating the interior of the knee than does cutting the knee open to inspect it. One of the important points to take away is that the diagnosis of CCL disease or rupture is not confirmed until visualization of the CCL is performed.

In rare cases of suspect “partial tear”, the CCL is found to be normal on inspection and some other problem is identified, such as an isolated torn meniscus in dogs, posterior cruciate ligament rupture, or cartilage injury. These other causes of lameness are far less common than CCL disease, but they can occur.

Treatment for Canine CCL Rupture

Once the CCL is ruptured and the femur is sliding off the back of the tibia we need to try and stabilize the knee. In humans, they would replace your ACL. In dogs, we have not had good or consistent success doing this even though veterinary surgeons have been trying to do so for many decades. It is likely that the substantial (30 degree) slope of the dog tiibal plateau causes breakdown and rupture of any material we use to replace the CCL. In addition, dogs are not very good about resting and doing rehab for 6 months. As a result, veterinary surgeons need to treat these patients differently. The most consistently successful and most commonly performed surgery by board-certified surgeons is the tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) operation in dogs.

Why TPLO Surgery is the Best Treatment Option

Unlike traditional knee surgeries that rely on ligament replacement, TPLO repositions the tibial plateau to create natural joint stability, eliminating the need for the damaged CCL, making TPLO surgery the best treatment for dog ACL/CCL injuries.

TPLO surgery offers:

- Higher success rates than extracapsular repairs

- Faster recovery and reduced long-term arthritis risk

- Permanent stabilization, even for active or large-breed dogs

Below, read more about how canine TPLO surgery works, what the TPLO recovery timeline is like, and how it can help your dog get back to a happy, active life.

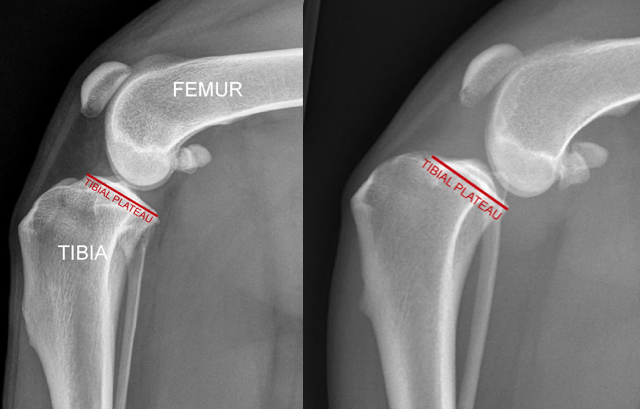

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO Surgery)

We have already discussed above how the tibial plateau is sloped downhill and backwards by about 30 degrees in the average dog. In order to prevent the femur from sliding off the back of the tibia we level the top of the tibia. We do this by making a semi-circular cut in the top of the tibia and rotating that portion of the tibia until the plateau is now leveled. We then have to secure the tibia with a bone plate and screws (similar to how we treat a fracture). The femur then sits back on top of the tibia instead of sliding off the back of the tibia. Please see the next images.

The image above shows a tibial plateau that is sloped backwards at about 30 degrees and the femur has slid off the back. A semi-circular cut (ie osteotomy) is made in the tibia and is shown by a black line in the image on the R. The top segment is rotated until the tibial plateau is now between 0-5 degrees (as shown on the right). A bone plate with 6 screws is then applied to hold the tibia in this position. Now the femur sits back on top of the tibia again as is shown in the image on the right.

Canine TPLO Surgery Recovery

Once the surgery is performed the bone (tibia) needs to heal. This takes time, typically about 10 weeks. Below are a series of X-rays showing dog TPLO surgery recovery week-by-week. Note that we usually do not take X-rays at multiple time points following TPLO surgery, but this patient was part of one of Dr. Franklin’s published research projects closely evaluating bone healing, so multiple radiographs (X-rays) were taken for those patients.

Figure. Dog TPLO surgery recovery week-by week. The images above show a patient immediately prior to surgery, immediately following surgery, and then at 4, 7, and 10 weeks following surgery. What we can see is that where the bone was cut was still visible at 4 and 7 weeks following TPLO surgery but that this had filled in with new bone (ie was healed), at 10 weeks following surgery.

TPLO Surgery Recovery Timeline

The following is a broad overview of the timeline of TPLO surgery recovery and does not serve as a set of specific discharge instructions. Detailed discharge instructions are provided to pet owners separately.

Since the tibia (shin bone) has been cut and stabilized, the first major objective following surgery is to have the tibia (shin bone) heal without complication. It usually takes bone 8-12 weeks to heal with most dogs having substantial healing by 8 weeks post-operatively. Additional time is needed for the dog to reach their full potential. A brief review of post-op dog TPLO surgery recovery:

-

- 2 weeks post-op: The incision is healed. The dog should be bearing weight (with a limp) on the limb at this point most of the time when walking.

- During month 1: The patient is allowed to walk about 15-30 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb >90% of the time when doing so by the end of the first month.

- During month 2: The patient is allowed to walk 30-45 minutes per day (on leash) and should use the limb the vast majority of the time, although not normally.

- 8 weeks: Radiographs (X-rays) are usually checked at about this time to make sure that the bone is healing appropriately and most dogs have about 85% healing of their bone at this point in time.

- During month 3: Most dogs can have extensive leashed walking, jogging, and hiking during this month. Brief, moderated, and supervised periods of off leash running can be started during this month.

- End of month 3: Dogs are usually released to unlimited activity at the end of month 3.

TPLO Surgery Prognosis

The prognosis with TPLO surgery to treat dog ACL tears/CCL disease and injuries is excellent. Approximately 94% of owners of dogs treated with TPLO ultimately report a good or excellent outcome.

Potential Complications of TPLO Surgery in Dogs

Major complications with TPLO operations in dogs are infrequent. Dr Franklin has performed thousands of canine TPLO procedures dating back to 2009 and his re-operation rate is currently less than 1%.

However, numerous complications with TPLO surgery are possible, and include infection (most common), tearing of the meniscus weeks or months following TPLO, incisional complications like bruising or fluid accumulation, fracture of the tibia, inflammation of the patella tendon, anesthesia-related complications including death, and others.

CCL & TPLO Summary Points

-

- CCL disease is the most orthopedic abnormality in dogs

- Physical exam, radiographs (X-rays), and visualization of the dog’s CCL, preferably with minimally invasive arthroscopy, are all important in confirming a diagnosis of CCL disease.

- TPLO is the most thoroughly researched and supported treatment of CCL disease (or “torn ACL”) in dogs.

- Prognosis with TPLO is excellent and major complications are infrequent but all owners should be aware of the possibility of complications.

- TPLO recovery period is 3 months with the dog having minimal, moderate, and substantial activity in months 1, 2, and 3 respectively.

Why Choose Kansas City Canine Orthopedics for TPLO Surgery?

When it comes to TPLO surgery for dogs in Shawnee, KS, Kansas City, and nearby areas, our mission is to help dogs recover faster, regain mobility, and enjoy pain-free, active lives. At Kansas City Canine Orthopedics, we are dedicated to providing advanced orthopedic care backed by years of experience, knowledge, and precision. Our team specializes in tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO), ensuring your pet receives the highest standard of surgical care for cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) injuries.

Pet owners trust us for:

- Experienced orthopedic surgeons with a proven track record in TPLO procedures

- State-of-the-art surgical and diagnostic technology for precise, effective treatment

- Minimally invasive arthroscopy to improve diagnostic accuracy and recovery outcomes

- Comprehensive post-op support to ensure a smooth, successful rehabilitation

At Kansas City Canine Orthopedics, our mission is to help dogs recover faster, regain mobility, and enjoy a pain-free, active life with the most advanced TPLO surgery available in the Kansas City area.

Schedule a Consultation Today

If your dog is showing signs of CCL disease, early intervention is key! Contact Kansas City Canine Orthopedics today if you have any questions about dog TPLO/ACL surgery or would like to schedule a consultation with our orthopedic veterinary specialists. Let’s get your pet back on their paws!

Veterinary Services

Below are all of the veterinary services we offer at Kansas City Canine Orthopedics. If you have any questions regarding our services, please feel free to call us.

Basic Structure of the Canine Knee

Basic Structure of the Canine Knee